Thursday, January 10, 2008

A Few Words On Sir Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Hillary, the man who made the first ascent of Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, died today. Here is what I wrote to the Nacirema Drinking Society:

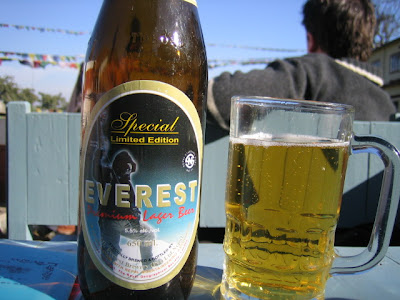

This is so strange. This is a man who was profoundly influential on my life. The first thing that inspired me to climb was the book High in the Thin Cold Air, by Ed Hillary. On the cover was Amadablam, the mountain that inspired me to climb mountains. In fact, I was writing a blog on this topic, still unfinished, just this morning. I read everything that Hillary had written prior to ever lacing up a pair of boots. Hillary always reminded me of my dad. And here I am, in Nepal, Hillary's true home (he was the New Zealand ambassador and did a ton of work on the schools here) and most likely even drinking Everest beer, with Tenzing on the label, when he dies. Life can be poetic in the oddest sense.

I would recommend Chang as drink of the month but am afraid I'd be the only one who could procure some. In lieu of anything else particularly Hillary-esqe, I'll second a Beefeater martini and I'll find myself a few later this evening. After all, he was knighted by the Queen.

"I don't remember much about those seven days (stuck in a snow storm on Cho Oyu) except that somewhere around day 4 or 5 George (Lowe, Kiwi not ours) came over, stuck his head inside my tent and said, 'You know, Ed, some people wouldn't think this was fun. (sic)"

This is from memory from one reading of his first autobiography, Nothing Venture, Nothing Win (now out of print and nearly impossible to find), back in the early 80s. Influential is no exaggeration.

So tonight raise a glass to one of the most important people in my life who, at least, is directly responsible for me spending a good portion of my life in the thin cold air.

Cheers Ed. Ya done good, mate.

Everest View

I’m not sure if I’ll ever travel again without at least some sort of athletic agenda. No matter what I’m distracted by, I spend most of my travel time wanting to be active. Conversely, I think the only way that I can relax and actually enjoy my new experiences is if I’ve been able to placate those demons that keep demanding that I push my body to the wall.

Yesterday I finally got a free day in Nepal and needed to do something that would hurt. I’d inquired with some trekking companies but they didn’t seem to understand my needs. The major treks from this area were all too long (15 days to Everest Base Camp) to be seriously contemplated in a day. The minor ones all seemed way too easy.

One of the minor treks visited an “Everest view point” in the range outside of town. It involved a two hour drive to the start and a pick up at the end. None of this sat well with me. However, looking at the course on the map I could see how it might be good on a mtn bike. So I decided to have a go at it.

I found a shop that rented mountain bikes and began going over their stock. I felt like an old west gunslinger picking a weapon as I brushed aside the sales clerk and began rifling through the bikes. I looked at components, tires, condition of each bike before choosing one. I gave it a quick once over, inflated the tires to the proper pressure, then rode it out the door, down the steps, did a bunny hop turn in the hallway and rode back in. The entire process had taken me about one minute. “I’ll take it.”

They gave me a map and inquired about an itinerary. “Nagarkot viewing platform,” I said. His reply was to ask me how many days I needed the bike. “What time do you close?” He tried to tell me what I was trying was “not possible” so I just said “maybe I’ll go somewhere else then. See you before 5,” and was off.

I hadn’t been on a bike in a month and it felt so good I can’t even describe it. I rode into the crowded streets of Thamel and began what was, essentially, a trials ride (for me) through the traffic. Out of the inner city I hit commuter traffic, which was a hoot. Driving in Asia is rather crazy. There seem to be no rules at all. But, as I’ve said before, a survivalist world is one that I thrive in and I’m quit certain that I was the fastest moving vehicle in Kathmandu yesterday. I bobbed and weaved my way through carts, busses, autos, motorcycles, and trucks. This “Sega game”, a term made up by some French guys who we’ve been hanging with who travel around on motor bikes continued for about an hour until I reached the tourist town of Baktapur.

Outside of town thing began to slowly change. I gradually moved up out of the smog and into open countryside. My breathing, which has been erratic and clunky for most to the trip, began to normalize. I stopped coughing for the first time in weeks. As I gained elevation I became more and more at ease and soon my body felt like it was reaching a state of homeostasis for the first time since I’d been in Asia.

My bike, a low-range Giant mtn bike, was perfect. It made me again realize how much money we waste on the highest grade of components and other silly stuff. This bike probably costs less than my friend Dustin spends for monthly upgrades on his race bike. And it was fine. It was reasonably light, well tuned, shifted and brakes well, and the pedals turned without interference. Sure, I’d be a touch faster on something else but no amount of money could heighten the experience I was having.

My first break was when I crested the hillside and got my first fairly close view of the Himalaya. It was breathtaking. A bus of Bulgarian tourists stopped and spoiled my solace, but it at least offered a chance to get a photo with me in it. One of the women looked around and asked, “are you alone?” After my affirmative and that my destination was “wherever the road ended” she added “you don’t mind being up here not knowing where you’ll sleep?” Man, haven’t any of these people ever heard of the Tour de France? I was probably only 30 or so kilometers and 3,000’ above Kathmandu. You’d have thought I was in Tibet.

The final climb up to the viewing tower had some seriously steep pitches and my legs were getting wobbly. It took actual effort to ride it non-stop, which was exactly what I wanted. Unfortunately, the clouds were rolling in and my Everest views were a bit skewed. The place was trashed, literally, and kind of depressing. But you could still see the majesty of the range—and this was a range I’d been reading about since I was a kid. I was okay with the downside.

On my descent I explored some dirt roads and found some off swanky hotels with Himalayan views that were filled with rich-looking tourists sipping cocktails or something. I’m not sure why but this blew my buzz. It all seemed so… Imperialist or something. So I headed down.

The ride home kinda sucked. Dropping back into the pollution was pretty miserable. It made me want to go home to my mountains. I was just wearing normal trousers and had decent saddle sores, which weren’t helping. I also hadn’t eaten and had a little bonk going. I only perked up once I got back to my bike messenger-esque riding through traffic where I felt it my duty to remain the fastest vehicle on the road.

I turned the bike in at 4:30. The guy asked where I rode. I told him but am pretty sure he didn’t believe me.

The Sound of Infinity

In my youth I read a lot about India, almost all of which centered on the spiritual. Stories of Imperialists were often rousing good fun but it was the sacred side of India that captivated me. The side the read the Upanishads, the place where Buddha become enlightened, where Maughm’s character from The Razor’s Edge finally exorcised “polite” society to discover the truth in life.

The India I finally arrived in was slightly different. A cacophony of sounds and smells perhaps unlike anywhere else on earth. If India is the spiritual center of the universe it must be because it’s so difficult to be spiritual here. Ones entire existence can easily be filled with nothing but distraction. Driving is more hazardous than a demolition derby. A simple walk can have you literally shaking beggars off your limbs. Your clothes become so dirty that you either wash them daily or just stop caring. For the average westerner, it’s a full scale assault on every one of your senses.

I spent my first week or so in one place and, soon enough, was rolling with it. India just became another place where anything was possible. It had good things, bad things, stuff I loved and stuff I loathed. By the time I was to leave Kolkata, I’d declared it my favorite polluted city on earth.

But touring was different. Kolkata, while mad and crazy and frantic seemed real. Out on the tourist’s path the assault was direct intervention. It was calculated. It was boring—a bit like Disneyland gone apocalyptic. I hate tourists and I never wanted to be one. Now I was.

Christmas at the Taj

Still, seeing the Taj Mahal seemed worth a sacrifice. This monumental expression of love was something it would be hard to be in striking distance of and ignore. Sure, the story may have involved some less than stellar people exploiting thousands of others for their selfish, over-the-top lifestyle, but who was I to judge a life that happened centuries ago? I wanted to experience it for myself.

But the idea of viewing it with thousands of others didn’t appeal to me. Night tours were said to be unpopular so I was hoping to catch one but, apparently, they were so unpopular that they were no longer an option. Then I heard about the sound of infinity.

The Taj is flawlessly constructed and the main chamber is said to be acoustically perfect. However, given there are hoards of people in it virtually every second its open experiencing this is difficult to do. Apparently if you do get yourself some time alone you can experience something called “the sound of infinity,” which is a subtle “whoosing” sound made when air circulates through the chamber. This sounded like it could evoke something of spiritual India. Now I just needed to figure a way to make it happen.

Our guide would pick us up at 6am, which I’d heard was when the Taj opened. Being India, the freest country in the world, I knew it would open whenever someone with a key was motivated to let people in. So I told everyone I’d see them there, then got up around 4 and went for a run.

I was surprised to see people on the streets at this hour. And even more surprised to pass a few runners. By the time I approached the Taj things were already bustling. At the gate my heart sank when I saw a short line of people being let inside.

With no other option I bought my ticket and kept running. The main viewing/photo op area was a zoo of people setting up for the sunrise. Beyond this, I was alone. I checked my shoes and found my way up to the main chamber. I couldn’t hear a sound as I stepped through the entrance. And then, “Please sir, I am guide.”

I politely refused but the guy wasn’t having any. He kept talking. His voice echoed beautifully off the ceiling but I that’s not why I was there. When I finally got him to quiet down someone else walked in. I moved around to the back and was still as possible and tried to hear through them. The sound in this room was incredible. The guide chanted “om” towards the ceiling and it was the most moving om I’d heard. But it wasn’t why I was there. I stood totally still and quiet and waited. Then they both walked out. I was alone.

It took a while for the sound to stop reverberating off of the walls. When it finally did, there was still a sound. A faint whoosh filled the chamber: the sound of infinity. Subtle, beautiful; it constantly changed based on any movement. I closed my eyes and tried to empty my head for a second. It was magic. It was also strangely familiar.

It dawned on me that I’ve heard this sound before; in the mountains. It’s almost the exact sound of standing alone on a summit on a clear quiet day. The subtleties were different but everything else felt the same. I could see why this was so moving to people. Most never see, or feel, a summit. And others the do are rarely alone. In my life, I get to hear the sound of infinity constantly. Perhaps it’s why John Muir described the first ascent of Cathedral Peak as “the first time I’ve been to church”. The mountains were my cathedrals. No human could rebuild them. A moment later the guide was back with another client, chatting incessantly.

I walked outside and ran into Jayda, a girl I’d met in Delhi who was traveling through Asia alone. I told her about the “sound” but when we went back in the crowds had gathered. The chance was lost until closing. We then found my family. They’d missed it too. Though they didn’t really understand they seemed genuinely happy that I’d done whatever I was attempting.

The crowds intensified—loud, obnoxious; more worried about how they looked in photos than trying to experience the grandeur of the monument. My sister’s boyfriend, a photographer, shared stories of the sunrise photo madness where an American—“of course”—had placed himself in front of everyone and refused to even crouch so others could get photos—his is overt disdain for anyone else’s problems only placated by a guard wielding a shotgun. I had enough of the crowds and, without a word, I slipped away.

Walking back to the hotel I was approached by a rickshaw. “Please sir, nobody is allowed to walk in India. Get in.”

“What about Gandhi,” I countered. “Didn’t he walk everywhere?”

The kid looked disgusted and with a wave of his hand was off. Yep, India had changed. But amongst the madness I found my moment of magic. It would have to be enough.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)